Lessons learned from the Spanish flu pandemic that we could apply to COVID-19

Elizabeth Stephens, The University of Queensland

Australia’s coronavirus public health messaging has been criticised as confusing during a time when health guidelines and regulations are changing rapidly, and educating the public about health is more vital than ever.

The slow roll-out of its public information campaign of videos and posters, urging people to wash their hands and keep their distance, has also been criticised.

But we’ve known how pandemic public health messaging works since the 1918 influenza pandemic, a largely forgotten, but important historical precedent for the current crisis.

We know from 1918 that pandemic public health messages need to be communicated widely and clearly, and to be consistent with government messaging and policies.

For this, messaging needs to be regulated by centralised, government agencies.

So which lessons has Australia learnt from the past?

Communicating widely works

Public health education campaigns have long played a pivotal role in managing public health, especially in moments of crisis.

Public health education, as we know it, is just over a century old. It is a product of the first world war, when more soldiers died of disease than injury.

Many of the earliest public health education campaigns focused on curbing the transmission of infectious diseases, more specifically, using posters to warn about venereal diseases (sexually transmitted infections).

But there are only a handful of posters warning about the influenza pandemic of 1918, which would go on to kill 50-100 million people, many times more than the war itself.

Partly this is because influenza broke out during the final stages of the war, when national resources were stretched thin.

It is also perhaps because it was initially overshadowed by that other great epidemic disease of the 19th century: tuberculosis.

However, as influenza spread around the world with returning servicemen in 1918, efforts were made to slow its transmission through new public health education initiatives, such as distributing information flyers.

The US city of Philadelphia, for instance, distributed 20,000 flyers warning about the transmission of influenza in 1918.

At the same time, however, it also decided to proceed with a large public parade, which attracted 200,000 thousand people.

Within three days, every hospital in Philadelphia was full. By the end of the first week, 2,600 people had died. Six weeks later, over 12,000 were dead.

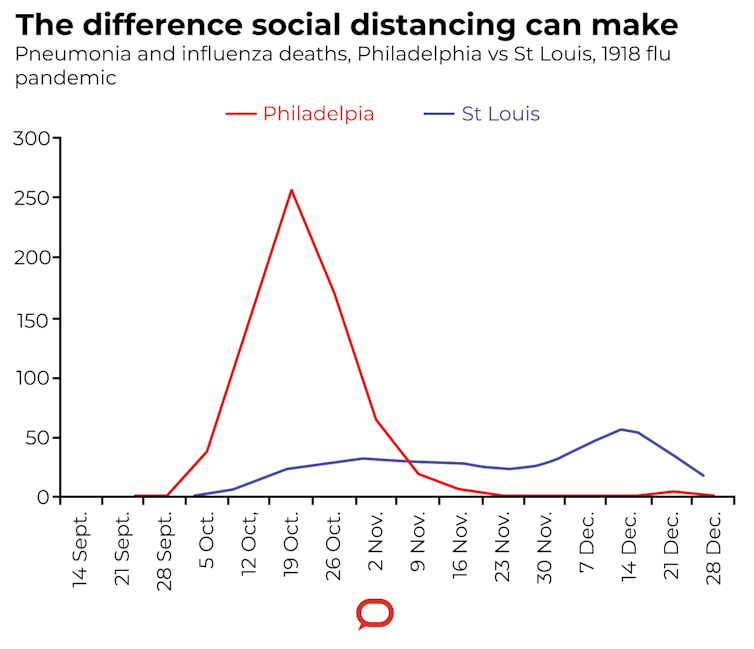

But the city of St Louis moved quickly to introduce measures like the ones we see today: shutting schools, cinemas, churches, and businesses. Some 700 died.

The difference between Philadelphia and St Louis is one of the most important lessons to learn from the 1918 influenza epidemic: “flattening the curve” works to limit transmission of infectious diseases, minimising the impact on health services.

It’s a message that’s been stressed in the current health messaging, not only by government, but by medical professionals and statistical modellers.

Current public health messaging to “flatten the curve” has had a demonstrable effect on public behaviour, encouraging widespread social distancing and self-isolation.

However, this message was undermined by what many perceived as the government’s slowness in introducing social distancing measures as a containment policy, and mixed messaging around their implementation.

In the middle of March, as events like the Melbourne Grand Prix seemed prepared to go ahead, some feared we were watching another Philadelphia in the making.

Effective government health messaging helps stem misinformation

Before the launch of the Australian government’s public education campaign, a wave of posts from the public on social media urged people to wash their hands for 20 seconds and physically distance from older relatives.

Millions of people watched the video of Arnold Schwarzenegger feeding carrots to a miniature donkey and pony, while encouraging his audience to stay inside.

And in the UK, a 17-year-old boy created a popular online tool that adds 20 seconds of your chosen song lyrics to a poster on hand-washing.

These examples represent something new: public health messages produced and circulated by the public, perhaps one of the most significant legacies of COVID-19, changing a century of practice in public health education.

While such initiatives are doubtlessly well-intentioned, they have moved public health education from government agencies and traditional media online, into a largely unregulated space.

Inevitably, we are seeing the circulation of medical misinformation.

This was also evident in the unregulated health sector of 1918, with a flourishing market in quack medical treatments, including ones that contained arsenic, camphor or mercury.

One of the key lessons of the 1918 influenza epidemic was, precisely, the importance of efficient and regulated public health communication.

This led directly to the foundation of national health organisations and media outlets. In the UK, the Ministry of Health was established in 1919, the BBC in 1922. In Australia, the Department of Health was established in 1921, the ABC in 1932.

However, with health regulations changing daily and announcements often made late at night, we need to ensure public health communication keeps pace with government health policy, and public messaging about both is clear and consistent.

How about future health campaigns?

The coronavirus is pushing so much of life online and the digital sphere grows more culturally influential.

To stem misinformation, robustly funded and well-resourced government health agencies and government public information campaigns are more important than ever.

During the current crisis, we have the opportunity to learn from the past, while taking advantage of new possibilities.

For instance, government health education can make greater use of social media to explain changing public health policy and regulations.

As Australia prepares for an extended and unprecedented period of mandatory self-isolating, ongoing clear and consistent messaging will be more important than ever.

Elizabeth Stephens, ARC Future Fellow and Associate Professor of Cultural Studies, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.