After decades away, dengue returns to central Queensland

Cameron Webb, University of Sydney

The Queensland city of Rockhampton was free of dengue for decades. Now, a recent case (May 2019) of one of the most serious mosquito-borne diseases has authorities scratching their heads.

Over the past decade, dengue infections have tended to be isolated events in which international travellers have returned home with the disease. But the recent case seems to have been locally acquired, raising concerns that there could be more infected mosquitoes in the central Queensland town, or that other people may have been exposed to the bites of an infected mosquito.

What is dengue fever?

The illness known as dengue fever typically includes symptoms such as rash, fever, headache, joint pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain. Symptoms can last for around a week or so. Four types of dengue virus cause the illness and they are spread by mosquito bites.

Once infected, people become immune to that specific dengue virus. However, they can still get sick from the other dengue viruses. Being infected by multiple dengue viruses can increase the risk of more severe symptoms, and even death.

Hundreds of millions of people are infected each year. It is estimated that 40% of the world’s population is at risk given the regions where the virus, and the mosquitoes that spread it, are active. This includes parts of Australia.

Read more: Explainer: what are antibodies and why are viruses like dengue worse the second time?

The last significant outbreak in Australia occurred in far north Queensland in 2009, when more than 900 people were infected by local mosquitoes.

Only a handful of locally acquired cases have been reported around Cairns and Townsville in the past decade. All these cases have two things in common: the arrival of infected travellers and the presence of the “right” mosquitoes.

The dengue virus isn’t spread from person to person. A mosquito needs to bite an infected person, become infected, and then it may transmit the virus to a second person as they bite. If more people are infected, more mosquitoes can pick up the virus as they bite and, subsequently, the outbreak can spread further.

Why are mosquitoes important?

Australia has hundreds of different types of mosquitoes. Dozens can spread local pathogens, such as Ross River virus, but just one is capable of spreading exotic viruses such as dengue and Zika: Aedes aegypti.

Aedes aegypti breeds in water-holding containers around the home. It is one of the most invasive mosquitoes globally and is easily moved about by people through international travel. While these days the mosquito stows away in planes, historically it was just as readily moved about in water-filled barrels on sailing ships.

The spread of Aedes aegypti through Australia is the driving force in determining the nation’s future outbreak risk.

The mosquito was once widespread in coastal Australia but since the 1950s, it has become limited to central and far north Queensland. We don’t really know why – there are many possible reasons for the retreat, but the important thing now is they don’t return to temperate regions of the country.

Authorities must be vigilant to monitor their spread and, where they’re currently found, building capacity to respond should cases of dengue be identified.

Read more: Is climate change to blame for outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease?

What happened in Rockhampton?

Last week, for the first time in decades, a locally acquired case of dengue was detected in Rockhampton, in central Queensland. The disease was found in someone who hasn’t travelled outside the region, which suggests they’ve been bitten locally by an infected mosquito.

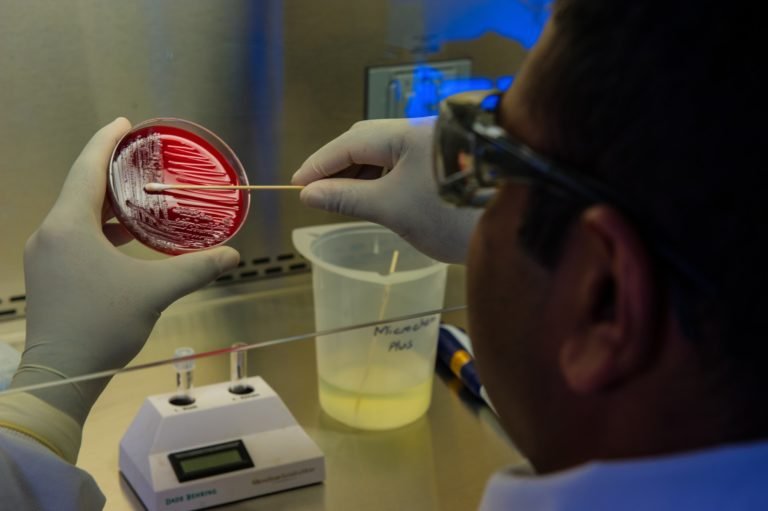

This has prompted a full outbreak response to protect the community from any additional infected mosquitoes.

While the risk of dengue around central Queensland is considered lower than around Cairns or Townsville, authorities are well prepared to respond, with a variety of techniques including house-to-house mosquito surveillance and mosquito control to minimise the spread.

These approaches have been successful around Cairns and Townsville for many years and have helped avoid substantial outbreaks.

The coordinated response of local authorities, combined with the onset of cooler weather that will slow down mosquitoes, greatly reduces any risk of more cases occurring.

What can we do about dengue in the future?

Outbreaks of dengue remain a risk in areas with Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. There are also other mosquitoes, such as Aedes albopictus (the Asian tiger mosquito), that aren’t currently found on mainland Australia but may further increase risks should they arrive. Authorities need to be prepared to respond to the introductions of these mosquitoes.

Read more: How we kept disease-spreading Asian Tiger mozzies away from the Australian mainland

While a changing climate may play a role in increasing the risk, increasing international travel, which represents pathways of introduction of “dengue mosquitoes” into new regions of Australia, may be of greater concern.

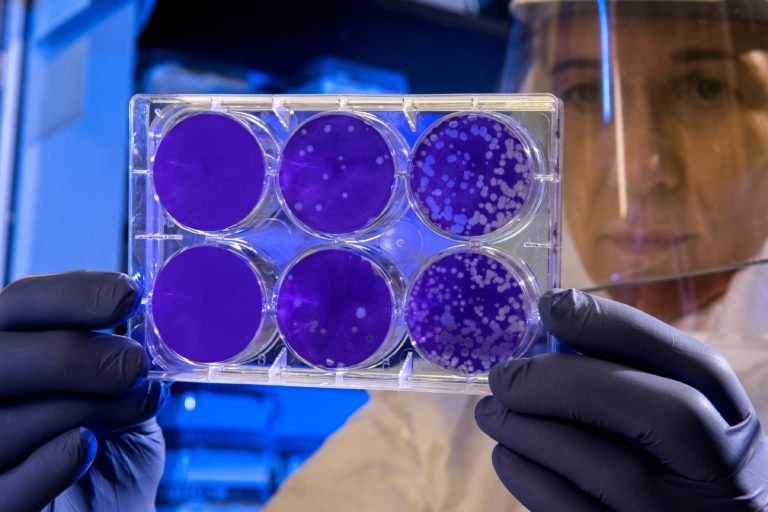

There is more that can be done, both locally and internationally. Researchers are working to develop a vaccine that protects against all four strains of dengue virus.

Others are tackling the mosquitoes themselves. Australian scientists have played a crucial role in using the Wolbachia bacteria, which spreads among Aedes aegypti and blocks transmission of dengue, to control the disease.

The objective is to raise the prevalence of the Wolbachia infections among local mosquitoes to a level that greatly reduces the likelihood of local dengue transmission.

Field studies have been successful in far north Queensland and may explain why so few local cases of dengue have been reported in recent years.

While future strategies may rely on emerging technologies and vaccines, simple measures such as minimising water-filled containers around our homes will reduce the number of mosquitoes and their potential to transmit disease.

Cameron Webb, Clinical Lecturer and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Feature Image: Wikimedia